Snow patterns on the South Coast

The south coast of BC (an area encompassing the Fraser Valley, Sea to Sky and Sunshine Coast) is known for rain in the winter months, and with altitude, snow. A rule of thumb states that every 1000 feet of elevation comes with a decrease in temperature of 1 degree. This old rule is mostly true, except in an inversion.

The south coast of BC (an area encompassing the Fraser Valley, Sea to Sky and Sunshine Coast) is known for rain in the winter months, and with altitude, snow. A rule of thumb states that every 1000 feet of elevation comes with a decrease in temperature of 1 degree. This old rule is mostly true, except in an inversion.

Temperature is an average of 2 degrees in the winter. What the 1 degree rule means is that 2000’ above Vancouver Harbour (sea level), almost all precipitation falls as snow. Flakes form higher up, and fall through various temperature layers; even when surface temperatures are above zero, snow can fall from higher elevations and stay intact. Thus, while Vancouver receives rain, the south coast mountains receive several meters of snow every year.

There are several recurring winter patterns on the coast that describe how this snow falls and what kind of snow to expect.

Winter Frontal Systems

The winter low pressure system develops off the coast of Vancouver Island and pushes inland. The “favourite” track is when the front travels across central British Columbia, with the trailing cold front moving southward across the south coast. This system is characterised by warm rain with rising freezing levels, bringing warm wet snow or freezing rain to 2000’ to 2500’ in elevation, followed by a cooling trend toward the end of the storm as the trailing cold front moves in. Depending on freezing levels, snow from these systems is heavy during the beginning of the storms and decreases as the temperature drops.

The winter low pressure system develops off the coast of Vancouver Island and pushes inland. The “favourite” track is when the front travels across central British Columbia, with the trailing cold front moving southward across the south coast. This system is characterised by warm rain with rising freezing levels, bringing warm wet snow or freezing rain to 2000’ to 2500’ in elevation, followed by a cooling trend toward the end of the storm as the trailing cold front moves in. Depending on freezing levels, snow from these systems is heavy during the beginning of the storms and decreases as the temperature drops.

The snowpack produced by a winter front is typically strong; warm wet snow in the lower layers, followed by lighter, colder snow near the end of the storm. This produces a dense, well bonded layer of snow, with a beautiful light, skiable upper layer. Backcountry skiers know this as “dust on crust”, especially when the dense snow came with high winds which can produce a crust.

The winter front, with variations, is the “business as usual” weather pattern for the south coast

Winter High Pressure Systems

The high pressure ridges are stronger in the winter, and bring clear, cold weather. The high pressure systems also bring inversions, as the cold air is trapped in valley bottoms. These are the times when winter recreationalists take to the mountains – after the storm has passed and the weather becomes stable again.

During times of high pressure, sun will melt the surface of the snow, which will freeze at night. If the high pressure lasts for a period of time, the resulting melt-freeze crust can become a “failure plane” for avalanches when the next snowfall comes and buries it. It can be common for this crust to become quite thick, especially when it is formed at the end of a winter front by warm snow or freezing rain. Thicknesses of 1 cm or more have been observed on local mountains.

During times of high pressure, sun will melt the surface of the snow, which will freeze at night. If the high pressure lasts for a period of time, the resulting melt-freeze crust can become a “failure plane” for avalanches when the next snowfall comes and buries it. It can be common for this crust to become quite thick, especially when it is formed at the end of a winter front by warm snow or freezing rain. Thicknesses of 1 cm or more have been observed on local mountains.

Also, during times of high pressure and clear skies and calm nights, frost can form on the surface of snow. This frost is known as surface hoar, and can be a big problem – surface hoar is the worst surface for a new snowfall to bond with, and can create persistent weak layers in the snowpack. The condition of a clear night is essential for the formation of these crystals; the snow surface radiates heat by a process known as black body radiation, and it becomes colder than the surrounding air; if the air contains any moisture this freezes on the surface. Perfect conditions for surface hoar formation include the above mentioned clear cold night, a moisture source such as a lake or stream, and very light wind or calm conditions to circulate the moist air over the surface of the snow.

Surface hoar is usually rare on the coast, except under fairly rare circumstances such as described below.

Arctic Outbreak/ Arctic Outflow

An arctic outbreak is when the relatively stable, seasonal high pressure that forms over Alaska and the Yukon pushes cold, dry arctic air southeast over northern and central British Columbia. This air usually moves into the Central Interior before stopping, and once or twice a year it spreads to the Southern Interior.

An arctic outbreak is when the relatively stable, seasonal high pressure that forms over Alaska and the Yukon pushes cold, dry arctic air southeast over northern and central British Columbia. This air usually moves into the Central Interior before stopping, and once or twice a year it spreads to the Southern Interior.

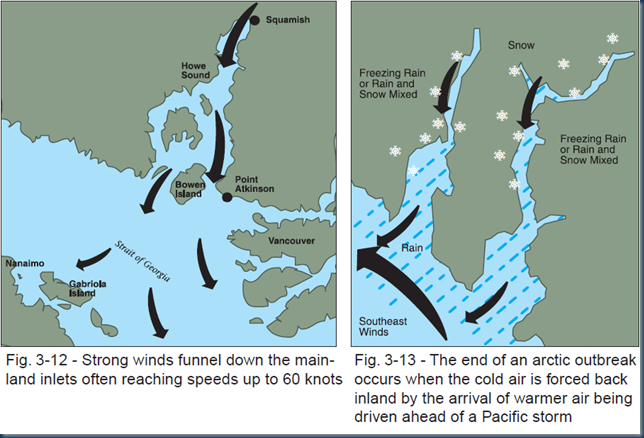

The outflow condition happens when the cold air pushes out from the interior of BC and moves through the Coast Mountains through the passes and coastal inlets, spilling out across Georgia Strait and the coastal waters to Vancouver Island and the Queen Charlottes. The outflow is infrequent on the South Coast, but when it happens it can persist for days. The names for the wind that come with this flow of air are recognisable as place-names of the BC Coast: Squamish Wind.

In local mountaineering and backcountry skiing, enthusiasts will recognise the outflow conditions as the times when features such as Shannon Falls freeze, and ice climbers can make an ascent. Several mountaineering routes in the south coast are only suitable under these conditions.

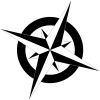

At the end of an arctic outflow, as a new warm front approaches from the pacific, snow begins to fall. Unlike the regular winter front, this snow can be quite light and cold due to the preceding cold air. The transition from outflow to inflow makes weather forecasting quite challenging due to the instability of the air masses and an inability to define where the freezing level will be hour to hour. However, snowfall during this time usually starts with cold light snow which gradually becomes heavy and wet and may transition to freezing rain. This period is also associated with high winds.

At the end of an arctic outflow, as a new warm front approaches from the pacific, snow begins to fall. Unlike the regular winter front, this snow can be quite light and cold due to the preceding cold air. The transition from outflow to inflow makes weather forecasting quite challenging due to the instability of the air masses and an inability to define where the freezing level will be hour to hour. However, snowfall during this time usually starts with cold light snow which gradually becomes heavy and wet and may transition to freezing rain. This period is also associated with high winds.

The movement from light, weak snow to heavy, dense snow results in an “upside down” snowpack where the stronger layers are on the surface, and weak layers are buries. Exacerbating this situation is the possibility of buried surface hoar which can easily happen after an extended clear and cold period.

Current Conditions

If you’re interested in backcountry winter travel, the avalanche bulletin is essential for determining the snow conditions. However, as the weather changes it is important to realise that conditions can change as well – even after the bulletin has been issued. Understanding the normal and abnormal weather patterns on the coast can help you predict what is going to happen to the snow. Also note that weather patterns in the interior are very different, but information on them can be found online (see references below).

If you’re interested in backcountry winter travel, the avalanche bulletin is essential for determining the snow conditions. However, as the weather changes it is important to realise that conditions can change as well – even after the bulletin has been issued. Understanding the normal and abnormal weather patterns on the coast can help you predict what is going to happen to the snow. Also note that weather patterns in the interior are very different, but information on them can be found online (see references below).

Note that today, November 26th, Vancouver has just reached the end of an Arctic Outflow period. We had a week of record breaking low temperatures, fairly clear skies and high winds, followed by slowly rising temperatures and a warm front. When the outflow started there was a light dusting of snow as the cold air chased away the preceding system’s moisture. As the outflow changed to an inflow, the weather forecast was unusually vague, and the snowfall warning was only issued in the day prior to the outflow ending – as the next front that came in was going to meet the mass of cold air. Vancouver and the Lower Mainland was blanketed with snow that was cold to start, and proceeded to freezing rain.

Note that the Arctic outflow was also responsible for the early opening of a number of ski hills throughout BC, including Whistler.

The avalanche bulletin for this date shows that the hazard for the sea-to-sky region is considered high, and the CAA has issued a special warning to this effect. The North Shore, in particular, is experiencing this unusual hazard. It is important to understand that it is not the large amount of snow that causes this hazard, but the arctic outflow conditions that result in an “upside down” snowpack.

References:

Climate of Vancouver, Wikipedia

Weather Patterns of British Columbia, NavCanada, Local Area Weather Manuals, Chapter 3

Arctic Outbreaks ©2005, Keith C. Heidorn, PhD. All Rights Reserved

Leave a Reply