How to Kill Yourself Snowshoeing

In 2009 my SAR team did a rescue on Eagle Ridge which made me realize something that all snowshoers need to know. I’ve noticed a trend in backcountry incidents that deserves mention; it has a clear cause, can be avoided by using simple techniques, and has gear and training that can mitigate the risk.

In 10 years of being a SAR volunteer in the Lower Mainland I have observed that the most common winter accident for a snowshoer or hiker is a slip and fall. In contrast to the rare avalanche, these are the incidents that result in a a team of 45 members being called out in the middle of the night to carry a subject out on a stretcher, or worse, in a body bag. I have been personally involved in the rescue of several people on Grouse Mountain, Mount Seymour and most recently on Eagle Ridge; all of them had snowshoes on and all of them slipped and fell. In one case I participated in a tragic body recovery for one of these accidents.

To clarify; these are incidents that involve a hiker or snowshoer where getting lost is not the cause for the search. In these incidents the pattern is that the subject slipped and fell some distance while travelling in the winter, on snowshoes, on foot or on crampons of some sort. I would also like to note that in the following I refer to snowshoers as the exemplars of this slip-and-fall phenomenon, only because in recent years snowshoeing has become more popular. It is important to realize that hikers, mountaineers and in some cases skiers are prone to the same slip-and fall accident.

Defining the problem

How big a problem is this?

I carefully analyzed 8 years of EMBC Incident Summaries looking for incidents where a snowshoer or hiker slipped and fell. I went through both the publicly available summaries, and the BCSARIS (BC Search and Rescue Information System) for more detailed analysis of the incident including the primary and secondary causes, modes of travel, and weather at the time of the incident.

The pattern I was looking for was as follows: snowshoeing, or hiking as mode of travel, and snow covered mountainous terrain. The primary or secondary cause had to be a fall, or the description of the incident had to describe and event or injury that involved a fall. I did not count incidents where a person fell in non-mountainous terrain (i.e.: crossing a log bridge). I did count incidents where the subject was wearing crampons. I removed incidents where the mode of travel was snowboard, even when a fall was involved since these are usually “out of bounds” rescues and do not fit the primary pattern. I did find one incident where a skier took a fall; this was included since it was a backcountry skier and the incident specifically mentioned the icy conditions as contributing to the injury, although the skier rescued himself.

I found 23 incidents that clearly fit the pattern of this type of accident since 2003, with a definite cluster of incidents in 2008 and 2009. There was a total of 25 subjects, 5 of whom were deceased, for a death rate of 20%. This compares to the death rate of 4.4% for all land-based SAR operations in the same period. The average number of subjects per task was almost one.

It’s interesting to note that almost no hikers or snowshoers were involved in avalanches during this period.

How do these accidents happen? Well, any accident involves four components: weather, terrain, gear and people.

The Setup: Weather

In my previous post on winter weather patterns I noted that typical weather patterns on the coast involve fluctuating freezing levels throughout the winter that produce frequent heavy wet snowfalls. Even in extremely cold weather, it is not unusual for a cold front to move through, bringing snow at the beginning and rising temperatures near the end of the storm. Sometimes this brings rain all the way to the top of our local maritime mountains. This regime is responsible for our (usually) very deep, dense and well-consolidated snowpack. What it also means is that there are long spells where the snow is so dense that snowshoes are not only unnecessary, but actually hazardous to use.

Winter weather patterns also include Arctic High Pressure and Arctic Outflow systems. Both of these bring clear, cold weather. The combination of rain to the tops of the mountains followed by low temperatures from these two systems happens at least several times each winter and results in a rain crust on the surface. In the spring, warm, sunny days followed by cold clear nights cause the same conditions; the surfaces of the snow melts a little each day, and freezes each night. This is called a melt-freeze crust. Local skiers call these thick crusts “boilerplate.”

The clear weather, sun and blue skies of a mid-season Arctic high, or a spring season day is extremely appealing to snowshoers. However, snowshoe trips in these conditions can be dangerous. The snowshoe, while appropriate for travel over soft snow, is not the most appropriate tool for travel on hard or steep snow.

The Factors: Terrain

The coast mountains are known for their “U” shaped valleys. Glaciation has flattened the valley bottoms and made the sides steeper. Subsequent erosion has cut gullies into the sides. This means that while we can easily drive to the top of the local ski hills to get to the snow, a few hundred metres in any direction leads to steepening terrain, gullies, and dangerous cliffs. In many cases ski runs and snowshoe trails run perilously close to the terrain traps.

Examples:

In the example presented below I show typical snowshoe routes on the three North Shore Mountains that have operating ski resorts. These routes are indicated in purple, and are a combination of officially cleared trails on private land, and marked park trails. I’ve indicated dangerously steep areas in solid red arrows (arrows pointing downhill), and gully systems that have seen many accidents in dashed red lines.

Hollyburn:

Snowshoe routes on Hollyburn Mountain: purple lines are ski runs.

Snowshoe routes on Hollyburn Mountain: purple lines are ski runs.

(click for larger image)

The snowshoe trails on Hollyburn mountain (near the bottom right of the above map) are an extremely popular and easily accessible destination. This does not mean that they are without risk. Indeed, snowshoeing to the top of Hollyburn or even skiing in the Cypress Mountain resort (on Strachan Mountain) takes you scant meters from a gully system that kills skiers and boarders year after year: the infamous “Australian Gully”. Gullies to the west lead down to the sea-to-sky highway and have also claimed several lives.

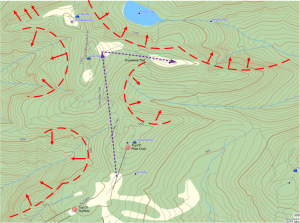

Grouse:

Snowshoe routes on Grouse Mountain: purple lines are snowshoe/hiking routes

Snowshoe routes on Grouse Mountain: purple lines are snowshoe/hiking routes

The official snowshoe trails on the top of Grouse Mountain are also easily accessible for day-trips, taking you on to the ridge to the east of Dam mountain. Several snowshoers have died here, (e.g. in fall, 2009), since metres from the trail are steep slopes leading down to Kennedy Lake.

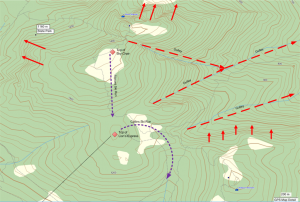

Seymour:

Snowshoe routes on Mount Seymour: purple lines are popular hiking routes

Snowshoe routes on Mount Seymour: purple lines are popular hiking routes

The park trails on Mount Seymour parallel the ski runs, but also thread their way past such features as “Suicide Gully” and the DePencier bluffs. In 2007 a showshoer lost his footing in an area known as Canada Pass and fell several hundred metres down a slope to Theta Lake. It took two days to rescue him.

Dangerous terrain thus exists within, and very close to, all three of the North Shore ski hills. Snowshoe for 15 minutes from any of the parking lots or lift lines and you can be standing at the top of a cliff. The steepness of the terrain and the presence of cliffs contributes to snowshoe accidents, making falls more likely (see below), and increasing the chance they will have catastrophic consequences.

The Gear: Snowshoes

Modern snowshoes such as the MSR Denali series are large platforms with a hinged binding and an optional tooth-like cleat just under the binding. When you strap in, your foot is in the binding, and the cleat is just under the toe and ball of your foot. The cleat is intended to handle the “hard snow” conditions found on the coast. The platform (in case you’re wondering how snowshoes work) provides surface area to distribute your weight across the snow surface, allowing it to support you.

Modern snowshoes such as the MSR Denali series are large platforms with a hinged binding and an optional tooth-like cleat just under the binding. When you strap in, your foot is in the binding, and the cleat is just under the toe and ball of your foot. The cleat is intended to handle the “hard snow” conditions found on the coast. The platform (in case you’re wondering how snowshoes work) provides surface area to distribute your weight across the snow surface, allowing it to support you.

This all works well when walking across level snow, or even going uphill. This is not when accidents happen. It is the downhill, or even worse, side-hill that causes snowshoers to lose their footing, slide, and fall.

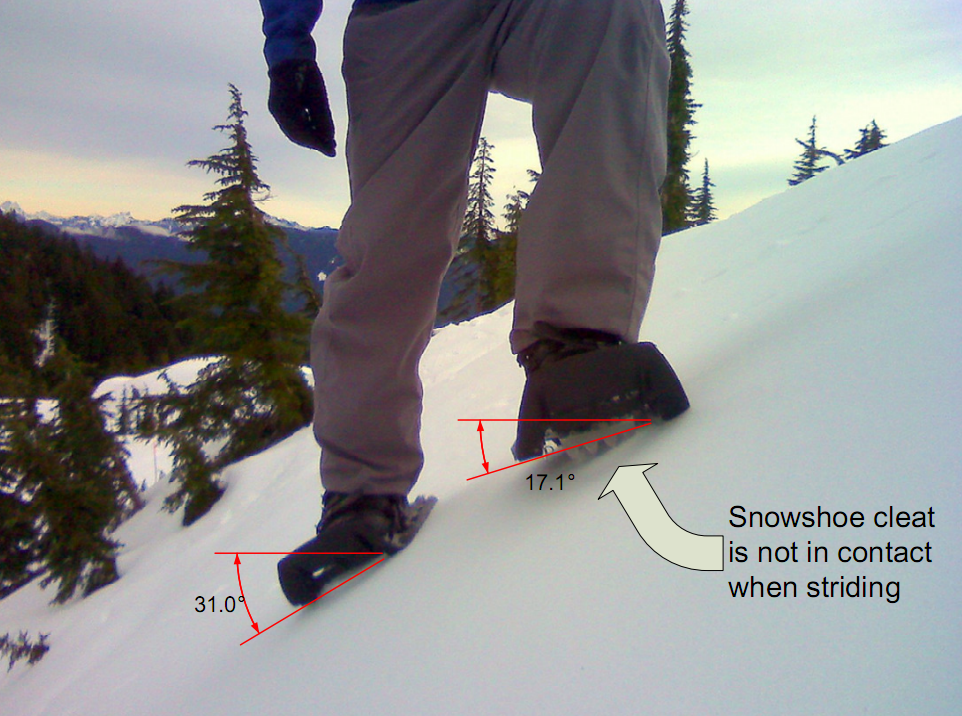

On the downhill, the platform that was so helpful on the way up is now your problem. While the hinge on the binding allows the foot to flex forward for uphill travel, on the downhill the heel of your boot is against the platform, and your foot is forced to point downhill parallel to the surface of the snow. As the terrain gets steeper, the foot points further down. The cleat, designed to help the snowshoe grip on the way up, doesn’t help as much in this orientation. In fact, for some snowshoes that have teeth that are slightly angled, the downhill orientation interferes with getting a grip and can cause the snowshoe to lose traction. Your natural instinct is to dig in with your heels, but this is exactly what the snowshoes are preventing you from doing.

Sidehill walking on snowshoes

Picture Copyright© Michael Coyle

On the the side-hill, the snowshoe platform causes the boot to twist sideways. Since the binding hinge is oriented for a forward and backward pivot, it can’t handle the sideways orientation. The user is forced to twist his or her ankles further as the slope gets steeper. The hiker’s natural instinct to lean into the the slope to maintain balance exacerbates the condition as it forces the ankle to twist even further. The sides of the foot put pressure on the platform of the snowshoe which can force it to “bite” into the snow on the uphill side while the downhill side levers out of the snow. This puts the hiker in a very unstable situation, trying to make forward progress while their platform teeters from side-to-side.

In both downhill and sidehill progress, each step is a risk. Every time the hiker lifts the snowshoe to step they have to stand on one twisted ankle. They cannot “dig in” with their heels, and are placing their entire weight on the poorly-designed binding teeth. As the free foot is lifted and moved forward there is the possibility of striking the standing leg, and making the situation worse. Finally, in the downhill mode, there is the possibility of the snowshoe swinging out and forward, moving the platform perpendicular with the snow. When this happens, the step “spikes” the snowshoe tail first into the snow, and the snow forces it forward. A tumble forward, head over heels, is quite possible at this point.

Although I place the blame on snowshoes in this section, hikers must also realize that they are in a similar predicament with regard to sidehills and descents; even kicking steps, putting one foot in front of another is a balancing manoeuvre and falls happen often.

While I have described the mechanical factors that lead to instability while snowshoeing, the above problems only happen when people travel in steep terrain. The next section details why people go there in the first place.

The Human Factor: Behaviour

There has been a huge growth in the popularity of snowshoeing in the past 10 years (Snowshoeing: From Novice to Master, 5th Edition), and it is not uncommon to see groups unwrapping new gear in the parking lot at any of the local ski hills. Snowshoeing is a simple, non-technical way of travelling on snow in the winter. The equipment is cheap relative to ski gear, requires no training to use, and for Parks and crown land trails there are no additional fees. So where is the problem?

There has been a huge growth in the popularity of snowshoeing in the past 10 years (Snowshoeing: From Novice to Master, 5th Edition), and it is not uncommon to see groups unwrapping new gear in the parking lot at any of the local ski hills. Snowshoeing is a simple, non-technical way of travelling on snow in the winter. The equipment is cheap relative to ski gear, requires no training to use, and for Parks and crown land trails there are no additional fees. So where is the problem?

The first is with the choice of destination. For many snowshoeing is an extension of summer hiking, and the snowshoes allow people to extend their hiking season to a year-round pursuit. The problem is that the destinations that one might easily attain in the summer are not the same in the winter. An experienced hiker may know trails in the area that are entirely within their abilities in summer, but which are inappropriate in winter. The ease of walking on snowshoes lulls the hiker into thinking that summer and winter objectives are pretty much equal.

Secondly, with the bush under several meters of snow, and a way to travel on it, snowshoers are free to go across country quite easily. In periods of cold clear weather with rain or sun crusts, or in the spring with melt-freeze crusts, the travelling can be quite easy. The temptation to leave the marked trail where hundreds of other have pounded the snow into a sidewalk-like hardness is overwhelming. Without a trail to guide them, and the false security of snowshoe cleats, it is easy to venture extremely dangerous terrain. Several of the incidents mentioned in the introduction were snowshoers who became stranded in steep terrain through just this series of choices.

I believe that the problem lies with the attitude that many people seem to bring to winter recreation; that it’s just an extension of summer recreation, except on snow. This could not be further from the truth. As the death rate of these winter slip-and fall accidents attests to, it’s much more dangerous that summer hiking in these same areas.

The solution: proper travel techniques

Snowshoes are designed for travel on flat terrain, do not let the cleats and teeth present on almost all modern snowshoes fool you. In icy conditions, as soon as the slope you are on reaches an angle where you can slide, (commonly accepted to be 20%), you are in danger. Without specific training and tools, a slip on hard snow results in an uncontrolled fall.

The solution is twofold; first, snowshoers and hikers must recognize the hazard when it happens. The simplest way to recognize the danger is to ask yourself if the slope looks steep enough that a toboggan would slide down it, or if you could ski it. If the answer is yes, the slope is likely steep enough that a slip could turn into a fall that cannot be stopped. Secondly, snowshoers and hikers must use the proper training and gear to mitigate the risk of skipping on steep, hard snow.

The techniques and training for walking on snow are well known to climbers and mountaineers. The primary technique for preventing a fall is known as self-belay. This is where a climber uses a tool such as an ice axe, ski pole, or other tool to penetrate the snow, and create a third point of contact. The goal is that if a slip happens, this will act as an anchor, and prevent a fall. The secondary technique is for stopping a fall and is known as self arrest. This is a technique where a climber uses an ice axe or other tool to rapidly stop a fall. Both of these techniques are covered in most mountaineering manuals, such as Freedom of the Hills, and all basic mountaineering courses, and are beyond the scope of this article.

The tools for travel on snow are the aforementioned ice axe, and crampons. Note that the publication Accidents in North American Mountaineering is full of incidents where crampon wearing, ice axe wielding mountaineers trip and fall, and are unable to arrest their falls. It is instructive to learn from others mistakes, and learn how to use this gear properly. Exceeding abilities and experience has been the cause of many tragic accidents.

Conclusion

The perception that winter travel is just as safe as summer travel is wrong. The perception that snowshoes are simple and easy to use is true, but the places you can go with them, although safe in the summer, can be extremely dangerous in the winter and spring. Snow on the ground makes for easy travel on flat terrain, but increasing hazard on steep terrain. Use of proper techniques for the season and the terrain can avoid accidents and deaths.

The solution to the snowshoe accidents described in this article are simple. There are well known, best practices for travelling on snow, regardless of season. Tools such as crampons and ice axes are designed to keep you from falling, and to stop a fall once it happens. Training and experience are required to know how to use these tools properly, and to know when the terrain is too steep for snowshoes or hiking boots alone.Travel techniques such as self belay on steep snow, rescue techniques such as crevasse rescue, and requisite training in avalanche awareness and avoidance are necessary for safe winter travel.

References:

Accidents in North American Mountaineering 1951 to present

Avalanche Accidents in Canada Vol4 1984-1996, also volumes 3, 2 and 1

Arctic Outbreaks ©2005, Keith C. Heidorn, PhD. All Rights Reserved

Snowshoeing: From Novice to Master, 5th Edition

The BC Weather Book: From the Sunshine Coast to Storm Mountain by Keith C. Heidorn

Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, 8th edition. The Mountaineers, Mountaineers Books, September 8, 2010, 592 pages, 7 1/2 X 9 , 978-1-59485-137-7

Regarding the problems with snowshoes while travelling downhill or on a sidehill, snowshoers should realize that they have the choice of orienting their foot in a different way to mitigate the problem. For instance, when travelling downhill you can turn around and "step backwards" down the hill, giving yourself the same traction you had when travelling up. Similarly when sidehilling you can face up the slope. In both cases some extra care is required to pay attention to where you are going as your vision may be restricted.

Great article! Having snowshoed for over 15 years,I personally love steep descents but they have to be deep as well.Hard and icy steeps do not appeal to me because they are ,as your article so aptly puts it,"dangerous".Ergo, not much fun for snowshoeing.Good point from Scott as i have used the exact method he describes when i have encountered hard packed conditions.I to, cannot stress how important it is to be self sufficient when out recreating in the winter time.I have seen too many people ill prepared.Snow shoeing may be "easy" but there is lots of tips and techniques to be learned not only of the sport,but of the conditions tthat are ever changing all season long.

Thanks agin for your article.

Dino Giurissevich

Avid snowshoer and snowshoe guide

Thank you for the very useful advice and well-researched backgrounder on the terrain in our back yard. So beautiful yet so deadly, eh?

It's amazing how so many of my trailrunning pals have taken up snowshoeing over the past few years. Such a natural crossover. So simple and inexpensive. No "user manual", though… so very easy for folks to get in over their heads. Looks like the incident statistics track the growth in popularity of snowshoeing and backcountry skiing.

If you don't mind, I will share your thoughts and advice on Facebook and http://www.clubfatass.com. Let me know if you'd like to do a safety clinic as a NSR fundraiser

Ean Jackson

Snowshoe runner and cliff-jumper

Thanks for the comments. Feel free to share the article, everything on the web site is under the Creative Common license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/

Excellent article! Having "rescued" a few snowshoers myself such as a naive inexperienced girl on Mount Seymour in trouble above some cliffs (short ones, not the big outside ones!) who had slipped and slid into some fortunately located trees, I can really attest to the ease with which people can get in trouble in well-travelled areas.

And don't worry, I am well enough experienced to assess a serious situation, stabilize the victim and call the professionals should a real rescue be warranted. I did once.

Snowshoes are NOT a substitute for crampons and axe.

At some point I’m going to publish an annotated list of the accidents I pulled for the database; the scenario you just mentioned (slip and fall, catch some trees) is in there as well.

thanks for the excellent article…really good points about how the local mountains can looks so tame yet the hazards are so extreme

Great article Mike. It is something I have seen and experienced since joining North Shore Rescue. There has been a big push to educate people about avalanche danger, but on the North Shore Mountains, falls are the bigger threat people need to worry about. I will definitely try and spread the word about your article.

Thanks for vindicating my descending steep slopes backwards. It is great to finally see an article that points out the problems with descents.

Regarding the above comment: descending steep snow slopes backwards while wearing snowshoes is not safe. It may be better than facing forward, but that does not make it safe. The reason is that the snow shoe prevents you from kicking steps deep into the snow. Self belay and crampons are best in such a situation The attitude that a compromised method will suffice is typical. Many snowshoers learn the hard way before routinely carrying crampons and axe. Most dont carry the gear. And almost none have Ast-1 training.

Great article. Forwarded to a few people who might be interested. Again, good to stick to the basics – do not venture out there in terrain and conditions that are beyond your ability and you do not have tools/training for.

Side-hilling while wearing snowshoes are my biggest nightmare. I recall having done a lot of it at Mt. Baker last winter, where sidehilling cannot be prevented in some steep slopes. The nightmare I mentioned is that my ankles twisted to the extent that I almost broke both ankles, which scares the crap out of me. I was also incapacitated whenever the twist occurs, making me afraid of actually falling or slipping down the slope (very steep – typical of Baker)Do tell how I can overcome the difficulty of sidehilling on snowshoes. thanks.

I was on Goat Mtn. when an accident happened (a year or two ago) where a snowshoer (from a different group) slipped and slid right down to Kennedy Lake. We helped make the 911 call, and SAR were there within 15 minutes. The body was retrieved soon after.

Snow conditions at that time were very icy, due to a long period with no snow. We had brought crampons, which were the perfect tool in those conditions – snowshoes were plain dangerous.

What I wanted to add is that I think the local hills, Grouse in this case, have a responsibility too. Some people take the lift straight up into the alpine, rent snowshoes and off they go. Sometimes they have never been out snowshoeing and know nothing at all about the dangers. Of course, some risks are always there, but in those especially dangerous icy conditions, I think some kind of warning should be issued, or perhaps snowshoes should not be rented out at all. It's true that people can still go out and buy/borrow snowshoes and circumvent this warning/no rental, but I think it could help.

Excellent article Mike. Another point would be to advise snowshoers of the actual snow conditions. As you pointed out, a hard icy surface is a recipe for disaster. Just as they have snow reports for skiing, there should be one for snowshoers. It could save lives…Just this past w/e there was another slip and fall at Cypress due to the icy snow conditions.

Hi Mike – as usual, a great article. And I was just about to buy snowshoes for my kids, too! Perhaps I’ll re-think, and buy crampons, or perhaps augment with an ice axe.

One note – the “Hollyburn.png” graphic is incorrectly linked to in your article — I did poke around some, and find the correct graphic at https://blog.oplopanax.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Hollyburn.png

Cheers!

Thanks for the feedback and the careful edit Charles!

Good article. Just a point that not all snowshoes are equal. Unfortunately people who want to get into the sport do not research and most often buy what those that are affordable and easily available. Check the snow shoes available at http://www.gvsnowshoes.com/en Most of their models have excellent crampons on the bottom and they have many different designs based on where one expects to use them. Regards. Ray

Ray; I don’t usually let a comment stand that explicitly promotes a brand or commercial operation but I am giving you a chance; what is it about the snowshoes being sold at this store that make them special?

Please note that I explicitly described snowshoes identical in construction to those pictured at that site, including naming the MSR brand (which they seem to sell), and that none of them address the failings described in the article.

Fantastic article! I’m glad to have found it!

As someone looking to start snowshoeing I’m trying to learn as much as possible to NOT wind up on the nightly news after needing to be rescued by SAR, or becoming a statistic.

It’s easy to think we know more than we do simply because we don’t know what we don’t know. This article was extremely helpful in making me start to realise just how much I don’t know! I’ll be sticking to the flat snowshoeing trails and learning more so I’m not just bumbling around out there unprepared! :-)

Thanks for the compliment, I hope all your adventures are exciting and don’t require SAR!

I assume that what you mean to say is that snowshoes are not designed well to go downhill on hard snow, which is an important safety point. However, it is false to say “Snowshoes are *designed* for travel on flat terrain.” The MSR Ascent Series snowshoes, for example, are designed for “all-terrain performance” with claims such as “unmatched traction in technical terrain,” “unrivaled grip—especially on traverses,” and “heel lifts” that “back you up when climbing the steeps.” That is, some snowshoes are intentionally designed for mountainous terrain. Snowshoes can be divided into design categories such as flat terrain, rolling hills, and mountain terrain. Flat terrain snowshoes (often tubular) are lighter and faster, having less traction and no heel lifts — making them more dangerous in the mountains.

Mountain terrain snowshoe work best when kept in a horizontal position or with all the sidewall traction planted firmly in the snow when side-hilling.

Concerning using snowshoes versus crampons on consolidated and crusty snow, this can be judged partially by the degree to which post-holing occurs without the snowshoes. In some crusty snow, it is important to move forward carefully and forcefully (kick stepping) enough to carve out flat steps in the snow as you go up the mountain. This can slow you down but greatly increase your traction and stability. Fitting trekking poles with snow baskets and adjusting them for the slope is also important for stability.

I completely agree about the dangers of going downhill in even mountain terrain snowshoes when the snow is too hard to flatten. In this case, the dangers of post-holing are preferable. Also, it is critically important to get out of snowshoes before you get on slopes too steep and hard to make the transition safely to boots with or without crampons.

On truly hard icy surfaces, even crampons with an ice ax can be too dangerous. That is, in some instances, you may never be able to self-arrest in time before going off a cliff or colliding at high speed into an unforgiving object. In these instances, you must know the limits of crampons and ice axes and avoid icy no fall areas!

Thanks for your comments Michael.

That line was designed to be deliberately provocative. I appreciate your feedback. I do understand that snowshoes do have features that mean they are designed for “steep terrain” – this is clearly technically true. I am sure that you can also appreciate that an inexperienced buyer of snowshoes could easily be led to believe the claims include all steep terrain and be unaware of the requirements of descending and sidehilling.

As a SAR volunteer I have personally loaded such a person, stiff, cold and very dead, into a body bag. I wrote the article hoping I could prevent a few of those.

Someone like yourself clearly has the experience and knowledge to understand the nuances of design and what techniques are required for different terrain. I’m very glad there are people like you out there dedicated to educating people!