Why you shouldn’t use Smart Phones for Backcountry Navigation

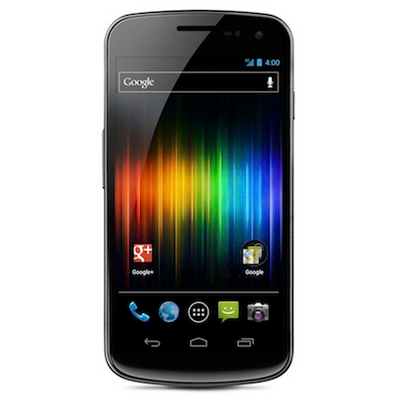

Smart phones are everywhere. By “Smart Phone” I’m referring to any mobile phone that has additional functions, but specifically for the purposes of this article a smart phone is any phone that has a GPS or A-GPS function. My assertion is that you should almost never use a smart phone in the backcountry as a navigation tool.

Firstly, I am going to leave aside all considerations of accuracy, time to calculate your position (get a fix), accuracy of map data and other things that are comparable in function and performance to other single purpose navigation devices. If you’re going to nit pick about performance, you can easily find a flaw in any GPS unit. In particular, flaws in the accuracy of the map data are well known and are common to every unit out there. Let’s assume that smart phones are in general about as good as any GPS with regard to basic function.

So why shouldn’t you use them for navigation?

Primary Function

The primary function of a phone in the backcountry should be always to call for help if help is needed.

Any use of the phone that could possibly impede your ability to call for help when you need to, whether it be for you or for another party, should be avoided at all costs. There are some common sense exceptions to this rule which I will go into a little later.

Why am I so hard and fast on this rule? Before the common use of mobile phones, people would be reported missing when they failed to return home in the evening. This would mean that a SAR team would usually be called out at midnight or 1 AM to begin a search, which could be several hours after the subjects became lost, or worse, injured. The team would search all night and usually either locate the subject during the evening or early the next morning once a helicopter could get into the air.

With the advent of cellular phones, many times people call for help immediately. If the person is lost, they can describe their route, and the scenery, and can sometimes be guided back to a trail without the SAR team even looking for them. If the subject is hurt, the team can react knowing the general area, and the type of injury. This saves time and lives by allowing the SAR team to react quicker. Now some of our searches and rescues are over mere hours after the incident occurs.

The mobile phone is the most useful way to get help when you need it, and can be considered a standard safety device to take with you on a hike; easily as important to a modern hiker as a map or compass (but not a replacement)

Issues

Battery Life

The most important reason not to use a phone as a navigation device is to preserve battery life. Smart phones are notorious battery hogs, and rarely get more than one day of use out of a single charge. Using the the GPS increases CPU load, keeps the screen on, and activates the GPS receiver. In addition, most mobile navigation software makes use of online maps such as Google maps, so the data connection also needs to be on to access the internet. this clearly drains the battery faster.

One possible exception to the battery life issue is if you have a spare battery. Most people do not, and it is well known that the most popular smart phone brand has no way for the user to replace the battery without voiding the warranty. There are special cellphone charging devices that can extend the life of your smart phone battery, but their weight and expense tells me that you would be better of buying a single-purpose wilderness GPS instead.

If the phone must be used consider turning off all unnecessary functions such as Bluetooth, and if possible mobile data (although as stated above, most software needs mobile data for the maps).

Ruggedness

Smart phones are also notoriously easy to damage. They are not waterproof, hard to use with gloves, and cold weather decreases battery performance. Taking them out all the time to consult them for your position just increases the chance that they will be damaged by water, cold or other environmental factors.

Accuracy

Despite major claims by equipment manufacturers, smartphone GPS is not as accurate as a wilderness GPS.

Finding your position

SAR teams can use your phone to help find your position. The first and simplest way we do this is by talking to you. At night we can ask what you can see, and teams approaching you can use flares to figure out where you are in relation to them. In the daytime we can ask if you can hear the helicopter searching for you. We can also give you advice on how to stay warm, and how to be easier to find.

The second, more advanced way is that the cellular network, under certain circumstances, can tell us your position by asking the phone to send it. This is not an easy task because it involves asking the police to get the phone company to get the position. It`s also not reliable because some of this function depends on the position of the phone relative to the closest towers, and if reception is bad it could also take a long time. However, it is possible, and it is sometimes extremely accurate.

The final, and most unlikely method of being found is that the light from the phone`s screen can sometimes be seen by a helicopter flying at night. Do not rely on this because most helicopters can`t fly over wilderness areas at night, and a fire would make a much better light anyway.

For more information on how a SAR team can locate you, read about some software I wrote to assist in that respect.

Exceptions

There are always common sense exceptions. These are important.

- If you are calling for help and you don`t have a regular GPS, then use the smart phone to find your location and tell the operator.

This should be obvious, but there have been at least two searches I have been on when a lost subject actually had a real GPS but neglected to tell the 911 operator, or any SAR managers. the search went on for many house before he brought it up. - If you`re just need to make a choice between two trails, or something simple like which way is north, then use the Smart Phone.

It`s better to use it a little and not get lost, than to steadfastly follow the rule and need to call for help later. On the other hand, if you find yourself needing to use it more and more often, then consider that you`re probably already getting lost, and you should use the phone to call for help before you run out of batteriesIn this case it is a judgement call as to whether the phone is more useful for communications or navigation

Recommendations

- If you are a hiker, buy a purpose-built wilderness GPS and learn how to use it

- Always have a map and compass as well – for when the GPS batteries die!

- When hiking, turn off your mobile phone especially if it is a smart phone, to preserve batteries.

- Keep the phone dry and, if possible, warm.

- If you must use it, use it sparingly, and use your judgement to determine when to call for help.

Summary

If you are a hiker, then you should not use the smart phone as your general navigations device. It should be held in reserve to to call for help and to communicate with SAR if there is a problem. Using the phone runs down the batteries and makes your best chance at calling for help less and less useful. Navigation is best done with a purpose-built wilderness GPS with updated maps, or a paper map and compass. Sparing use of the Smart Phone in an emergency to provide SAR with your position is recommended, as is very occasional use to provide minor guidance.

Even though I stress that the mobile phone is your best chance of calling for help, remember that they need to have a line-of-sight view of a cell tower for them to work, and the distance from that tower is also a factor. There are many areas very close to Vancouver (in particular Buntzen Lake) that have extremely poor or no cellular reception

I recommend these procedures for using smart phones and cell phones because I know they are ubiquitous, so almost all hikers have them. Retaining battery life is the only way of being certain you can make a call if the reception is good enough. I cannot recommend cell phones as a reliable method to call for rescue because of the reception issue.

Very good advice. A smart phone is only a tool, a very powerful tool when needed but it must be able to function to work. No one would think of leaving a flashlight on all day and then be surprised when it did not work at night.

that`s a great analogy, and by chance most smartphones have a flashlight app in case you didn`t bring one.

True story; we once rescued a group who were using the light on their GPS as a flashlight to hike down the trail. And yes, they were crouching and moving very slowly.

Search and rescue teams are actually starting to adopt the use of smartphones with the right kind of navigation apps – as they offer capabilities that really aid in planning, recording, coordinating, and reporting on incidents. See http://www.viewranger.com/SAR

Anonymous; certainly with the caveats that you need to have backup batteries, and have a waterproof case for the phone, I can see using this solution. However, there are many other hurdles that make it impractical.

I am sceptical that a volunteer SAR team would see the benefit of purchasing software, batteries, and cases for members that could have any one of hundreds of different brands of smart phones, and supporting and maintaining the installation of software on such phones.

Having managed all of the equipment for a team of 45 members for five years, I can tell you that the maintenance of a fleet of devices is no small matter. I have also worked in IT, and no manager would make this choice. The simplicity of deploying a standard wilderness GPS to each member gives you redundancy in case one breaks down or runs out of juice.

This of course leaves the member's mobile phones in the pack where they can be used to back up the VHF radios in areas of limited coverage.

I suspect the rescue teams in that list have their logo on the page in exchange for free software that one or two members use. I can see where this might be useful in a vehicle, or in a command centre but not for wilderness searching.

Your argument that you should save the battery for making emergency phone calls does not make sense. Given the less than reliable cell phone service in most wilderness areas, it should be a last ditch effort, not a primary plan. On the other hand, attempting to successfully navigate should NOT be a last ditch effort but a priority. Most people are far more likely to be able to use a smart phone successfully for navigational purposes than call for help anyway, and if it’s a matter of helping you find your way and avoiding needing to call for help (because you are lost or because you got off route causing something else bad to befall you), that seems to imply that using up the battery for navigation purposes is far better than trying to save it for something that may or may not work. Also, many people carry some sort of emergency locator beacon, which is generally far more reliable in summoning help or providing your location to the outside world.

If navigation is a priority then use a device with an external antenna, accurate, rugged, waterproof, and is built for navigation.

Using a cell phone to navigate is like using a jack knife to chop down a tree. A serious back country enthusiast will have a map, compass and wilderness GPS.

Backcountry users have been successfully navigating all kinds of terrain without a GPS for a looooong time.

Navigation should always be a priority, shouldn’t it? However, one should not rely on a GPS or any other electronic device as their primary mode of navigation. A GPS or a Smart Phone is a supplement to map and compass, so if you already have a Smart Phone and not a GPS, why not use it for that purpose? It’s a hard argument to convince someone to purchase something that is not multifunctional and will cost them multiple times what a GPS phone app costs and that adds extra weight to their pack when it will be used as a BACKUP. And should you get in a jam where you do have to rely on a jack knife to chop down a tree, then that’s still better than not having a jack knife.

I think I wouldn’t have a problem with your post if it was titled “Why GPSes are better for backcountry navigation than Smart Phones.” Advocating for people to not use a tool they already have that does work in many circumstances, even if it may not be the best at that function, just doesn’t make sense to me.

Just because a smartphone has a GPS and can be used as a navigation device does not mean it should. That’s the distinction I am making.

As I posted elsewhere, the GPS in a smart phone is not as accurate as a purpose built wilderness GPS unit.

https://blog.oplopanax.ca/2012/11/measuring-smartphone-gps-accuracy/

Second, the biggest energy draw on a modern smart phone is the screen, which you use quite a bit when navigating

https://blog.oplopanax.ca/2011/09/smart-phones-and-battery-life/

Finally the phone is fragile, susceptible to cold and wet. If the weather turns, the phone is a big problem.

Solutions to two of the three main issues include external batteries and waterproof cases… but so far I have not seen a solution to the signal strength. As a side note, the “solutions” turn the multi-function device into a very heavy and expensive replacement for a simple wilderness GPS unit that takes the same batteries as your headlamp.

Since the GPS only does one thing, the batteries tend to last a long time; multiple days in some cases on long SAR tasks I have been on.

Most of the rest of my posting is based on 13 years of SAR work where people are getting themselves into trouble by trusting the smart phone to help them navigate. Most of them run out of batteries by noon or so. It’s clear that the people we rescue have suspect decision making skills, but one of the commonalities is that they have not thought through the consequences of using the phone as their primary navigation device.

I titled the piece as I did because I do not believe smartphones are appropriate for use as a navigation device, and the recommendation to buy a GPS is couched in as strong a language as possible. You’re entitled to your opinion of course, but I can see you agree that the GPS is better.

I assume you read the piece though, and see that I specifically made mention that if you do have a phone and nothing else then of course you should use the phone. To quote: “If you must use it, use it sparingly, and use your judgement to determine when to call for help.”

That said, what are you disagreeing with?

I’m disagreeing with your assertion that the phone is merely a last resort. I think it can be used to supplement map and compass, just like a GPS can (but less reliable). I think where the trouble is, which you point out in your description of SAR cases, is when people don’t understand the limitations of the device and rely on it to do something beyond its very clear capabilities.

But as a SAR person, and admittedly this is difficult to mitigate, you are overly exposed to the people that mess up, not the hundreds of others that did not need rescue that may be using smart phones to aid in navigation.

I must mention that you guys have a much higher caliber of subjects up there than we do. Most lost people we rescue have at best an incredibly vague idea of map and compass and GPS (and certainly almost never actually own these items let alone have them along or know how to use them), so we don’t have the issue of rescuing someone who was relying on their smart phone GPS app and it failed them. :-)

The way I see it is this

* if a phone is all you have then you’re not prepared.

* if you have a map and a compass and just use your phone a little, that’s mentioned in the article, but it’s not recommended.

* if you’re way back in the backcountry and you are still using just the phone then you are not prepared. Serious backcountry users should be taking a wilderness GPS if they want to supplement their navigation tools.

There is a middle ground, but I am speaking mostly to the uninformed.

It’s true I tend to *rescue* the unprepared and believe me I see my fair share of people using the phone as a flashlight as well (also not recommended).

However, I’ve consulted on backcountry adventure travel and taught basic survival and the common perception is that you don’t need a GPS any more. Many believe the phone replaces maps. Hence my messaging in the strongest possible terms so it is not misunderstood; turn the phone off and get the right tools for the job.

Good information, clickbait title. Sure worked on me.

This nine-year-old article seems out of date. Today, many or even most “smart phones” (are there any other kinds anymore?) are waterproof, power banks are cheap, small, and lightweight, there are offline mapping apps easily and freely available, which even contain elevation contours, and phone GPS units have come a long way in the nine intervening years. As long as the phone is used responsibly I can’t see why it isn’t as good as a dedicated GPS.

Possibly, some hiker behaviour has changed a little and people are using them more resposibly.

However, the fundamentals are still the same: the power density of batteries is still much the same. The GPS units in the phones are still less accurate than dedicated GPS with external antennas. The additional weight of an external battery pack is far greater than a wilderness GPS with a few extra “AA” batteries.

When you consider the cost of the phone and the additional accessories you need to buy to make it last longer and handle rough weather compared to the smaller cost of a simple rugged GPS, I still see the phone as inferior in almost every aspect. I recommend people invest in a GPS unit, paper maps, and keep the phone in reserve. We still rescue people all the time who have no battery life left.

I’ve really struggled with this because I bought a Garmin 64st GPS years ago cause I was under the impression it was more reliable but have ended up using my cell phone’s GPS app and have found it much easier to use and lighter weight. The GPS is quite heavy in comparison and goes through batteries like crazy. It is so frustrating, 2 AA might last 2 days if I’m lucky. Instead, when going on multi day trips, I bring two phones (lucky to have a second work phone that is also waterproof), put them both in airplane mode and bring two battery packs including one with solar charging capabilities. It has served me quite well over the past few years. When looking weight wise, I’d be bringing my phone anyways and the battery packs probably weigh the same or less than my GPS. I do understand the concerns with too many people bringing one phone, no power backup, leaving it on so the battery drains as they text, take photos etc. and then end up in a bad situation. I guess I just wanted to note that there are ways to responsibly use a phone as a functional GPS. Or at least that is what I tell myself.

There are definitely ways to be responsible.

This article is quite old now and the train had left the station even before it was written. The only goal now would be to point out the flaws in relying on a single device that wasn’t built to handle the conditions found in the outdoors.

My personal opinion is still that a purpose built GPS is the best solution, alkaline batteries perform better in the cold, and that setup is more reliable and accurate. I’m not a big fan of needing to treat my devices like they’re made of china.

I’m not as familiar with the Garmin 64st but with the 62 series we found that the battery life improved a lot if you tuned off the digital compass. Given that we all carry compasses that don’t require batteries I’ve never seen the point of a digital compass.

I still feel like the hassle of bringing two phones and assorted charging infrastructure is a lot compared to a single GPS and a few extra batteries, I’ve done quite a few 10 day ski traverses with this setup.