On Outdoor Responsibility

I found an interesting site the other day: Leave No Trace (there is a Canadian offshoot as well). It’s a site that promotes outdoor ethics and offers guidance on the best practises to preserve wilderness values, and reduce the impact of self-propelled outdoor recreation on wildlife and the environment. If you’ve been following the blog you know I wrote about this with respect to group sizes a few weeks ago.

Strangely, these web sites don’t seem to place any stress on group size, but perhaps that’s because almost nobody would consider 100 people to be appropriate. Interestingly, they do have an entire section devoted to being considerate of others; ideas here include avoiding trips on holidays, making your cap site less obtrusive, etc. Some of the principles are frankly ridiculous, such as not wearing bright clothing, but it’s a good thing that they are promoting some good principles.

A New Principle

One thing completely missing from the leave no trace site is something that bothers me quite a bit; it’s a form of outdoor responsibility that is not related to the environment or being particularly considerate of others.

This is my new outdoor responsibility principle:

In any outdoor pursuit, plan to leave enough margin for error such that, barring accident or misadventure, you can rescue yourself or your companions.

To explain the principle, I’ll use the metaphor of an engineer building a bridge. The engineer chooses the materials and the design such that the bridge is strong enough to handle the loads it will experience; these being the traffic, wind, weather, snow etc. Not only must the bridge be strong enough to handle the predicted loads, it must contain a certain excess strength to handle corner and edge cases, or when there is a lot of snow, traffic and wind at the same time. Finally the bridge needs to have additional strength to allow for unpredictable forces, such as an earthquake. This final allowance is the margin of error – a kind of fudge factor to leave capacity on the structure for unpredictable forces, or errors in other calculations. This kind of building is why the Brooklyn Bridge is still standing even though it was built to carry horse and carriage.

If an engineer builds a bridge that does not conform to standards and best practises in the field, and does not allow for this margin of error, then the engineer is deemed incompetent; licenses are revoked, lawsuits are launched, and careers are ended. This is not to say that every failure is a result of negligence, or that all bridges need to be overbuilt like the Brooklyn, but standards and best practises must be followed

So it is with outdoor pursuits; any backcountry traveler can carry a tiny pack with only the most essential gear, but doing so is cutting down on the safety margin. Every backcountry recreationalist has a duty to prepare themselves, carry the right equipment, and know their own limitations. From my experience as a rescuer, it’s the last point, self knowledge, that is the hardest to come by.

Preparation

The first stage is preparation for a particular trip. This includes building the right skills, understanding the route, what travel modes are required, and physical conditioning. In addition, studying the weather, tides, avalanche conditions, researching the approach, acquiring maps, and studying the “escape routes” should there be a problem and you need to get out quickly. Often this includes preparing a trip plan or a safety plan that includes how to communicate in case of emergency.

During the preparation phase for bigger trips you will also study what time of year is best for a given trip, and what the go/no go conditions are. These are advanced skills, used for trips that require more advanced planning, but are applicable to even the shortest trip.

Equipment

Not enough equipment, not the right equipment, or substandard equipment that fails, all of these things contribute to narrowing the safety margin. Knowing how to use the gear is tied to the preparation stage (above). I have participated in rescues that are directly attributable to all of these causes.

The wrong equipment often results in injury and death. Being under the impression that snowshoes are appropriate for steep icy slopes, wearing shoes or runners for off trail travel, or mountaineering, or ski poles instead of an ice axe, and instep crampons in general; all of these are common causes for search and rescue response.

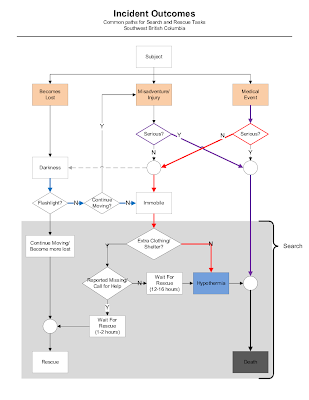

In the case of a small incident, not having enough equipment to spend the night (food water and shelter) often results in hypothermia, even in the summer. Not carrying a flashlight is an extremely common reason we are called out.

Finally, the push for ultra-light gear is quite distressing. Gear that may be useful for supported adventure races, or European hut-to-hut ski trips with good cell coverage are not appropriate for the BC wilderness. Some of this stuff (not all of course) is not tried and tested, or is designed for occasional or emergency use. Be careful when selecting gear.

Self-knowledge/over-extending

Over extending, or going beyond your abilities is the final area I’ll cover. There are two sub-categories.

The first is the subject that does not know their own limitations. From my own experience, I find that this area is the single most common reason a rescue is required, and it kind of trumps the first two (preparation and equipment). The people we rescue are very often the ones that do not know their own abilities, and they are not ready for the conditions they encounter. Not knowing the conditions or preparing properly, they are also deficient in the second area, equipment. An example is that locally, in the spring and summer, people are continually surprised by winter conditions at the elevation of the local mountains. Subjects are treated for hypothermia in the middle of August.

The second subject is the one that deliberately over-extends themselves in pursuit of a goal. This is quite rare, and I haven’t seen too many instances, but they happen. Examples that I find particularly irritating are those people who’s goal is self-aggrandizement, or fame. Example of this can be seen at any film festival, or in the pages of alpine journals around the world. In the pursuit of fame, or a first ascent, people regularly over-extend themselves, or “push themselves to the limit.”

Most of these people know exactly where their limits are. They also know just how far they can push, and often they have the skills and physical ability to do so in a safe and controlled way. Not everyone in the journals and films are unsafe. Here’s the problem; just watching or reading, you can;t tell the difference. Those who perform the greatest feats, whether responsible or not, are still “famous” in the community. Beginners and the general public can;t tell the difference.

If someone stops wearing a seat-belt, it does not mean that they are more accident prone, merely less able to survive should even a small incident happen. The fact that we seem to respect those who appear to do the most dangerous activities is the most disturbing, and the thing that leads less-able people to attempt their feats with less skill and preparation.

Reasonableness

I’m not advocating that each person carry a huge pack, an enormous first aid kit and a Sat-phone on every backcountry trip. That is just plain nuts. There is always some risk involved. For example, if we take the engineer metaphor as an example, the engineer cannot account for traffic accidents, nor can they build a bridge with a dedicated lane for emergency vehicles. It might be safer, but it is not currently reasonable.

However, on a multi-day trip a sat-phone and one large first aid kid are reasonable. A small injury can become life threatening if there’s not antibiotic available, and a sat phone can save your life. Also, as times goes and, gear gets cheaper, it becomes a standard. It’s now a standard for backcountry skiers to carry an avalanche beacon.

Each person or group has to take responsibility for determining what is a reasonable amount of gear to take. A few power bars, a pair of runners, a tarp and no map is not the correct way to approach a 10 day trip. Unfortunately, there is no professional body, such as there is for engineers, that can set and enforce standards in this way. Backcountry pursuits are still mostly taught by amateurs to other amateurs in traditional ways. The internet is the resource that can help determine what is reasonable, but of course there is also a lot of misinformation out there.

In a recent post on a local outdoor board I read a proposed solo trip by a forum member – one that was clearly over ambitions, with the wrong gear, in the wrong time of year (high avalanche hazard), and by someone who clearly could not tell that he was over extending himself. They could have completed the trip, but like in the seat-belt metaphor, they would not have been safe in doing so. Luckily, the members of the forum chimed in and convinced the member that this trip was not for them.

Consequences

The consequences of violating the principle are complicated.

Many rugged individualists might state that they do not want someone to rescue them, and that they expect to perish in their given activity if they fail. I suspect they subscribe to some world view where each person has complete responsibility for their lives. That’s all very nice, but people live in societies, and society has a duty to protect it’s members, even the self-destructive ones.

Practically, there is not DNR (Do Not Rescue) order that applies to the backcountry.

A person is reported missing, and in BC the police investigate. If they are in the wilderness, then they ask SAR to assist, and the search is on.

SAR members act using their training, equipment and best practises in their field, but there is always an element of risk that cannot be mitigated by safety equipment and procedures. SAR members risk their lives and well being; we choose to do this.

The principle is based on the idea that wilfully, or neglectfully endangering yourself by not allowing for a margin of error is akin to an engineer building a bridge not strong enough for the edge and corner cases – it is a form of negligence, and by this action you endanger the lives and well being of others weather you intend to do so or not.

We should not accord respect and fame to the people who “risk everything,” because they clearly are not just risking themselves.

Conclusion

For some people, the goal of self-knowledge is the reason they go into the wilderness. The paradox is that, except for the most mundane days trips, have to have some self awareness to survive in the first place. If we use the metaphor of the engineer, and hold that outdoor recreationalists of all types need to be responsible for their behaviour, and their own safety, then they should follow best practises in skill building, preparation, and gear selection. They should also consider that, by over-extending in the pursuit of a goal, be it a summit, or a first ascent, they are not just putting themselves in danger, but the lives and well being of those that would rescue them.

0 Comments on “On Outdoor Responsibility”