Death in the Backcountry

Continued from Part 1

(Copyright Michael Coyle, reuse with permission)

So I’ve been trained to dangle under a helicopter, and it’s fun. However, like a lot of things in SAR, it’s all fun until it’s for real. And this brings me to the second surprise I got when joining SAR: dead people.

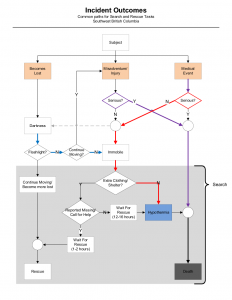

Every lost person usually starts as a healthy person. There are several routes that take them from a healthy person, to a lost person, to an injured person, to a dead person. Many become lost, and continue to move after dark. If they don’t have a flashlight, walking in the dark usually leads to injury, usually an ankle or lower leg which makes it hard to move. Immobility leads to hypothermia, which with time leads to death. There’s also the case where moving leads directly to death through falling off a cliff, or falling in the water.

The next category includes people who were never lost, but through misfortune became injured. This is usually falling; cliffs, small hills, etc. If the injury is critical, these people usually die rather quickly. If the injury is not critical, they are either dramatically slowed down, or immobilized. If slowed down, they are caught by nightfall, which leads to outcomes in the previous paragraph.

Finally there are people who have existing medical conditions; heart attacks, strokes, and diabetic events. When these happen in the backcountry, it’s pretty much going to turn out badly.

The commonality for all of these scenarios is that if you are in the wilderness you have two things against you: communicating your need for assistance, and the time taken to deliver that assistance. The best case scenario is that you have complete cellular coverage, a GPS, the weather is good, and you can make it to a clearing. This happens rarely, and when it does, SAR people call it a “Heli Hike” because the rescue is so easy it’s like flying for a pleasure hike. The average time for a rescue like this to unfold is about 1 hour, unless there are exceptional circumstances. Note that this is termed a rescue because there is no search.

However, lack of cellular coverage, thick canopy, bad weather and nightfall all contribute to an inability to communicate your need for help, our difficulty finding you, and the time taken to access your position. A complicating factor is that many people do not tell anyone where they are going, so when they do not return they are not reported missing. Also most people This can add a delay of 8-16 hours before SAR will even start looking.

I’ve come up with a handy diagram that illustrates the common events and outcomes resulting from a misadventure in the backcountry. You can see from the diagram that I’ve listed “Rescue” and “Death” as the two major outcomes (I’ve left off “never located”, I will cover that in another post).

The sad thing is that the “Death” outcome is a lot more common than I thought it was.

How does this relate to helicopter rescue?

The people who are the hardest to get to are often those who have, through misadventure, come to the grimmest ends. In the past few years I’ve been directly involved in the removal of two deceased students from SFU, a snowshoer on Grouse Mountain, a hiker in the Stein Valley, and a gentleman last summer near Lion’s Bay, just to name the recent ones.

On reflection, I think that one of the major themes of this blog, avoidance of requiring rescue, comes from my experiences of extracting corpses from the wilderness. Grim work, but I’m hopeful that my stories here are useful to someone.

I see a small problem with your flow chart. It appears that should you become lost, all you need is a flashlight to assure your eventual successful rescue.

My pack just became a lot lighter…..

Yes, I think the flowchart needs an article all on it's own. The flashlight is the difference between moving and not being injured, and moving in the dark.

People with flashlights seem to continue moving, those without either stay in one place or continue moving and injure themselves.

Probably needs a few more iterations. I think the three entry points are pretty clear though.

Actually, I think that inserting "incident specific factors" in each of the circles in the rescue phase with a dotted line leading to the opposite outcome would apply to most situations. If you state that most situations follow the common pathway, incident specific factors could change change the result, for good or bad.

Then list some examples,

Weather – cold, rain, snow, etc

Age – child, elderly, etc

Survial skills – food, water, shelter, etc

Self rescue – avi rescue, ability to swim, first aid, etc

Comorbid factors – Alzheimers, suicidal, developmental challenge, etc

Technical rescue – high angle, swiftwater, mountain terrain, etc

Personal preparedness – 10 essentials, etc

Search area – size, terrain, travel distances, heli access, etc

The flowchart is an attempt to identify common paths and outcomes to SAR incidents, and does not try to exhaustive.

It might be worth a few more articles on the subject. Outcomes for people who score higher on the scale (ie: adding points for each inclement factor such as bad weather, lack of gear, medical condition, terrain familiarity and objective hazards) would tend to be worse.